This video was part of a roundtable discussion involving surgeons Christina Y. Weng, MD, MBA; John B. Miller, MD; Raymond Iezzi Jr, MD; and Suzie A. Gasparian, MD. An edited transcript of the case presentation and discussion follows below:

Christina Y. Weng, MD, MBA: I’m going to cap things off by showing a complex case that I encountered a couple of years ago. I think this one cost me a few years of my life, but had a pretty good outcome at the end. This is another surgeon—a 48-year-old male with high myopia. He came to me with vision of 20/400 and a macula-off rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in his right eye with a tear at 7 o’clock and lattice inferiorly. I planned for an encircling primary buckle, but knew there was a chance I probably wouldn’t catch that tear and would have to add an element—and indeed, intraoperatively, I couldn’t catch it with the encircling band. So, I decided to add a radial 503 sponge. Unfortunately, when I was placing the posterior mattress suture, I perforated the sclera and it led to quite a large subretinal hemorrhage involving the macula.

I decided not to convert to a pars plana vitrectomy during that surgery. Instead, I injected 0.3 mL of 100% SF6 and positioned the patient face down for a week.

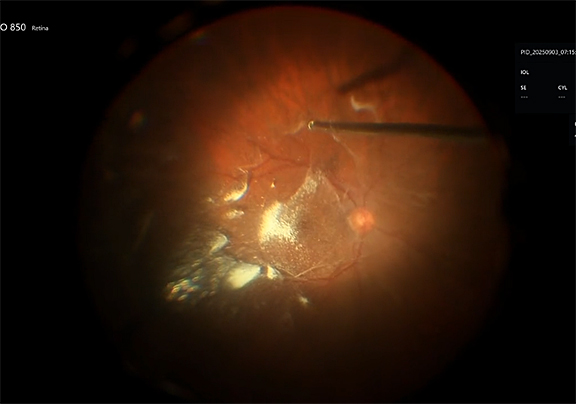

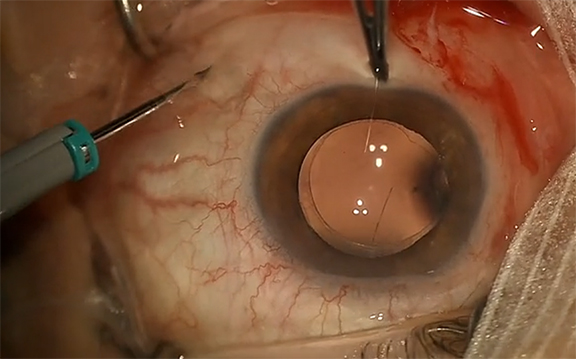

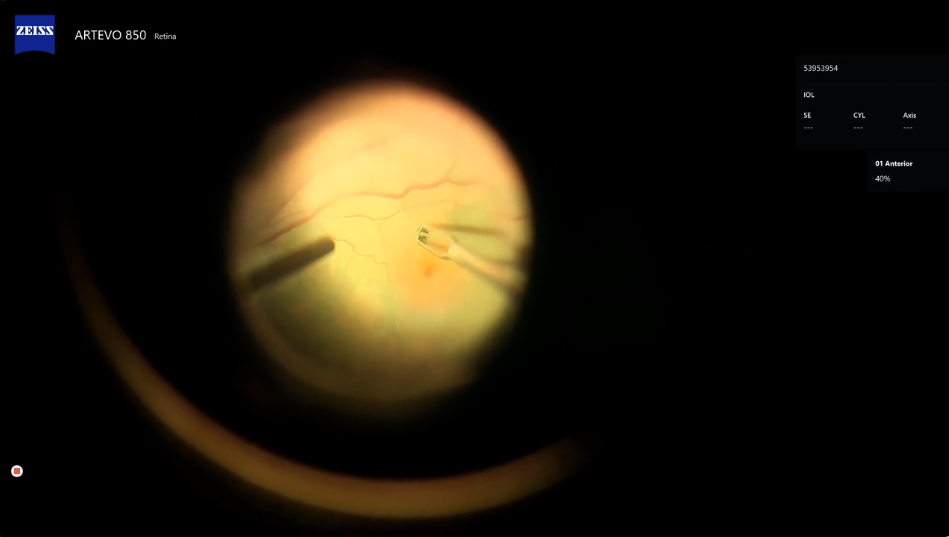

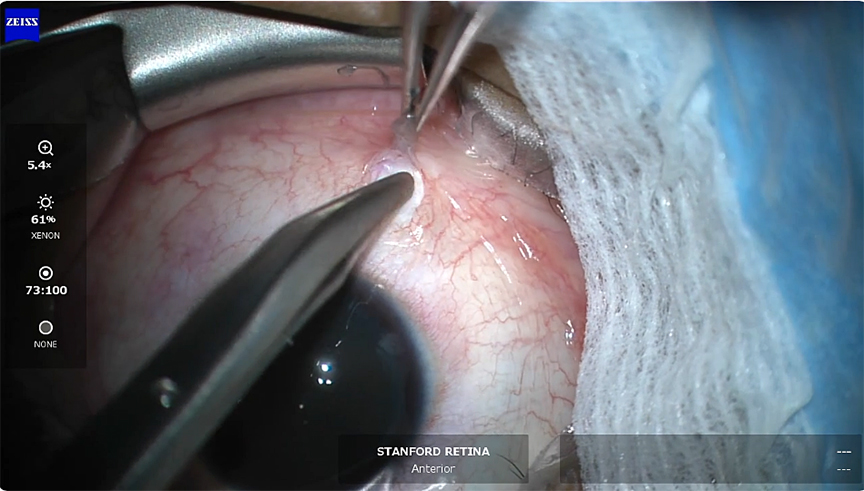

I’m going to show you that first video here. You’re going to see that he has a bullous detachment with that 7 o’clock tear—this is surgeons’ view—and I am going to first place the encircling 41 band. You can see I tried to place it pretty posteriorly but was not able to catch that tear at 7 o’clock. So I decided to add the sponge, but first I go back and mark the break and apply cryotherapy. You can see that it is quite posterior, and it is challenging to judge position when it’s this bullous. Here I am with the 503 sponge and as I mentioned, I unfortunately perforated the sclera during that posterior mattress suture pass. You can see going back in how large this subretinal hemorrhage is. Unfortunately, this is affecting the macula of this patient’s eye.

As I said, I decided to stop there. I ended up injecting 0.3 mL of 100% SF6 and I asked him to position face down in hopes that that hemorrhage would move out of the way.

Postoperatively, the patient ended up developing a dense vitreous hemorrhage. I was a bit uneasy because I no longer had a view and was not sure what was happening, but on B-scan, he looked completely attached so I fathomed that the hemorrhage was probably due to the subretinal hemorrhage egressing through the original tear at 7 o’clock. So I decided to wait it out while the retina reattached, and then returned to the OR 3 weeks later for pars plana vitrectomy.

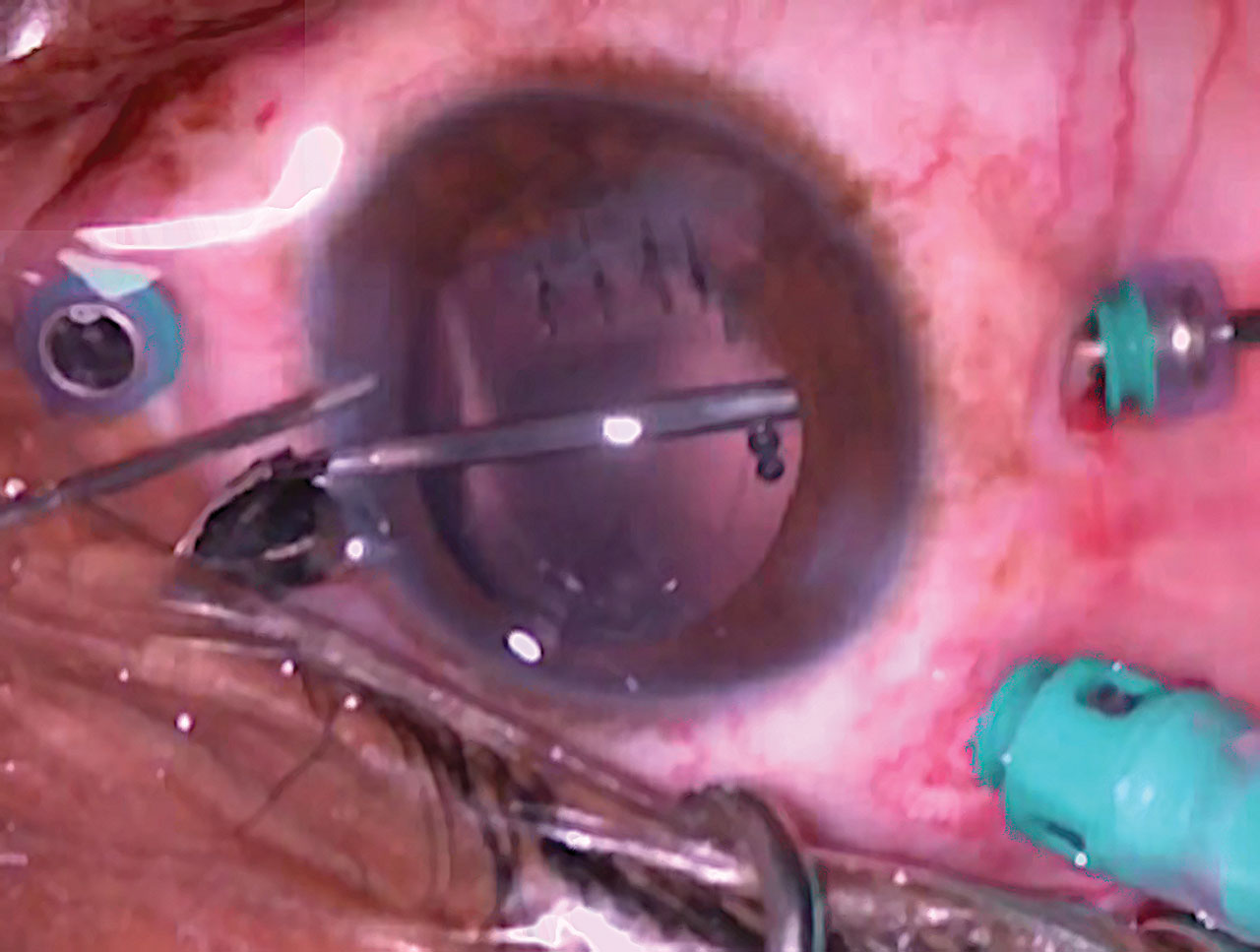

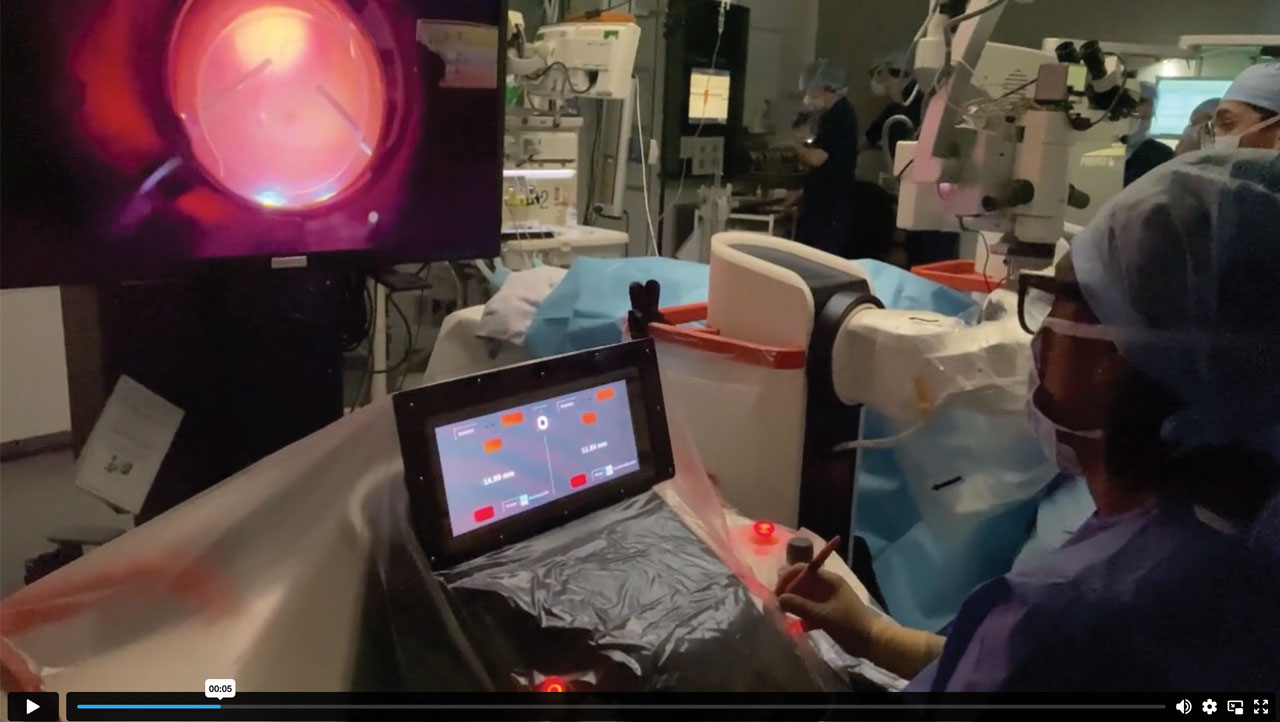

This is the second part of his surgery. I’m setting up in 25-gauge platform. Notice a very dense vitreous hemorrhage here. I’m removing the vitreous and you can imagine my happiness when I finally get to the back and I’m able to see that the retina is indeed completely attached. You can see where that element is at 7 o’clock. Remarkably, you can see that there is no longer any hemorrhage under the macula, and only a bit of residual heme along the posterior edge of the buckle. I did end up placing a bit of laser around that area—probably not necessary, but I just wanted to be extra cautious. And then I closed up.

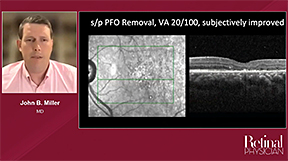

Postoperatively, his vision improved to 20/20 and his retina remained attached. It’s been a couple of years—I actually just saw him for his annual visit—and he’s doing really well and still able to operate, thank goodness. Lots of pressure when operating on other surgeons.

I wanted to use this case to really launch a discussion, because I think when you do surgery long enough, you’re going to experience every complication and that's what really makes roundtables like this so fun. You not only get to commiserate and exchange stories and validate experiences, but we also get tolearn from each other about how to manage these situations that you may not have encountered before and also talk about preventing them from happening in the first place.

The best treatment for subretinal hemorrhage is prevention! There are several susceptible steps during primary scleral buckling where this can happen, including subretinal fluid drainage, suturing of the buckle, belt loop creation—especially in patients who are myopic and have thin scleras. Suturing elements can be a susceptible step, especially if you’re trying to reach really posteriorly, because some orbits are very tight. And with cryotherapy, be sure you do not pull the probe away before it has thawed or else it can lead to a major subretinal hemorrhage. Any other tips from the group on preventing hemorrhage during scleral buckling? And how have you managed these situations in the past?

Dr. Iezzi: Christina, I have a question for you: Was this patient big? Was he obese?

Dr. Weng: He’s not obese but he is a very big guy.

Dr. Iezzi: I have found that reverse Trendelenburg is one of the best ways to minimize the risk for choroidal hemorrhage. I think what's going on is that the positive pressure on the thorax from the abdomen puts pressure on the vena cava, and they have a high venous drainage pressure. I think their choroid engorges. So, by having their feet down relative to their head, all the blood is rushing from their thorax, from their abdomen, and it's decompressing the eye to some extent, and they just hyperextend their head just ever so slightly. It's not uncomfortable. I have seen patients where one patient had a thoracic kyphosis and he was quite heavy up top there and I predicted the high risk of a choroidal hemorrhage. As the fellow was doing the primary vitrectomy, we saw a superior nasal choroidal hemorrhage develop and I took over. But this was one of those cases where we couldn't really effect the reverse Trendelenburg because of the thoracic kyphosis. It’s a technique I use to try to reduce that risk.

Dr. Miller: I think my lessons are just that this is going to happen, regardless of any of the techniques you mentioned—belt loop, scleral suturing, drainage—so I think you have to stick to best surgical techniques. When you're teaching or working with trainees, there are times where the actual pass or the belt loop would just be cut too deep. It will happen even if you do perfect technique—you have thin sclera or the vortex vein just happens to be in the same location where you’re trying to drain. I try to teach “move on to the next case, don't over-adjust your technique too much.”

I do drain every case, even though I have had one or two subretinal hemorrhages from draining. I try to avoid draining directly in the mid-quadrant, just given the predominance of that being a common area for vascular congestion. I try to drain just above or below the rectus muscles. If you do have a hemorrhage, I try to raise the pressure. If you have your buckle on, you tighten the buckle and tighten the sutures if you haven’t sutured them yet. Depending on where the hemorrhage is and how close it is to the macula, I would have potentially done a vitrectomy to try to clear the hemorrhage out of the posterior break.

I think you managed the case well. This is in that twilight zone when they’re 40 to 50 years old where you can really do a variety of procedures. Posterior break to me would usually trigger “more likely to do a vitrectomy,” because I know it's going to be hard to support it with the buckle. I don't do radial sponges, so I would have had trouble with my buckle techniques, getting this on the band.

Dr. Weng: It was definitely a borderline case. I thought it was going to be pretty posterior, but it is always hard to tell when the retina is so bullous. But a crystal-clear lens, no PVD, so I did end up doing a primary buckle, but you’re right he’s in that borderline age category and it is important to consent them for either of those procedures.

Dr. Gasparian: I think you managed the case very well. Some people, if there is concern for subretinal hemorrhage involving the fovea, they would attempt vitrectomy, but I think it’s appropriate to inject the gas bubble and have them position to displace any subfoveal heme, assuming that the patient can position well post-operatively. I think that converting to added vitrectomy may pose additional challenges in these instances.

Dr. Iezzi: I totally agree, Suzie. I think this was very brilliantly handled. I think that when you go in and do a vitrectomy, you’re inviting expansion of choroidal hemorrhage. During our procedure, our removal of vitreous, we’re lowering the intraocular pressure. Instead, what you did was you maintained a closed eye, you added gas—which increased the pressure—and you had a drain retinotomy to allow the blood to get out. So, you literally on a mechanical basis did a displacement of a very fresh hemorrhage through a hole in the retina that was ultimately supported. From a physical perspective, this was literally the ideal way to treat this. Going back and doing a vitrectomy for vitreous hemorrhage is a whole lot safer than a vitrectomy for an acute intraoperative choroidal hemorrhage. I think this was fantastic.

Dr. Weng: Ray and Suzie, thanks for those comments. I'll just make one additional comment. I think the scariest moment is when you’re in the middle of that first surgery and see this large hemorrhage forming. Or maybe you know the exact moment when you have perforated, but I want to add that sometimes these hemorrhages can be small and relatively contained. They don’t necessarily get humongous like this one and involve the macula. So like John said, the immediate thing you want to do is to prevent expulsion. If there’s any sort of full-thickness scleral wound, for example, you want to immediately release traction on those isolation sutures and suture things up. But then you want to raise the pressure to try to stabilize the hemorrhage. The other thing you want to try to do is to tilt the eye away from the macula. If you see bleeding happening, which is usually going to be around the equator where we're working or draining, tilt away from the macula. If it stabilizes and stays fairly contained, you can sometimes get lucky where it will not enter the critical macular territory.

Dr. Miller: I think the other thing to think about is that you rather quickly recognized you had hemorrhage, but in some cases you may not know. If you’re doing a vit-buckle, you may not know until you go in or you may not know until you look in to set the height of the buckle. Teaching folks to pay attention to the resistance that they feel as the needle is passing is important. I look for the speed at which the needle is going and if I see a sudden acceleration, that tells me, “Oh, the resistance is lost.” Either the pass is too shallow or it’s too deep. Depending on visual feedback of the wound, you can tell what’s happening. It’s worth taking a look in. Any time that the suture is too deep you want to try to repass it. You don’t want to leave it there. I would usually go a little bit anterior or posterior, depending on which pass it was, and then re-tie it in different location.

Dr. Weng: I appreciate that pearl. Thank you for the great discussion, and this concludes the case. RP