This video was part of a roundtable discussion involving surgeons Christina Y. Weng, MD, MBA; John B. Miller, MD; Raymond Iezzi Jr, MD; and Suzie A. Gasparian, MD. An edited transcript of the case presentation and discussion follows below:

Suzie A. Gasparian, MD: Thank you for the opportunity to present regarding the management of complex dislocation of in-the-bag intraocular lenses. This is a middle-aged male with a history of combined scleral buckle and pars plana vitrectomy with gas for repair of a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. He presented with dislocation of a single-piece intraocular lens.

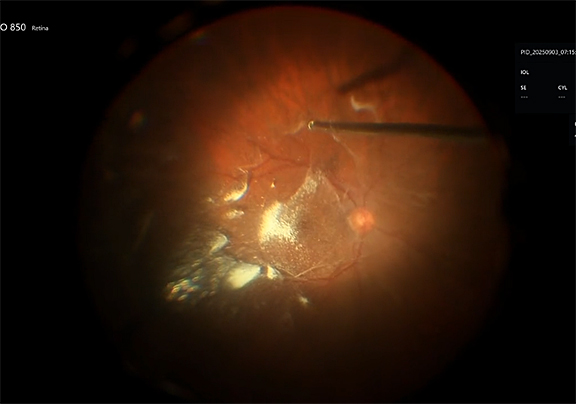

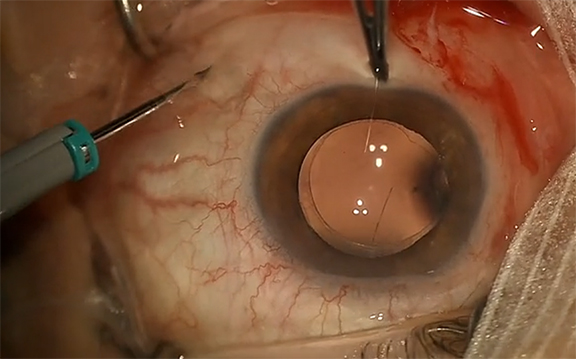

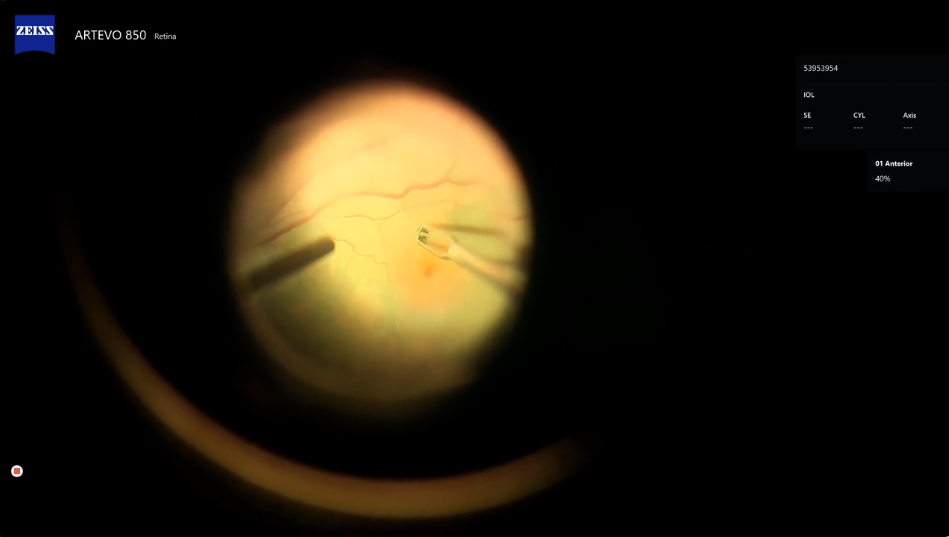

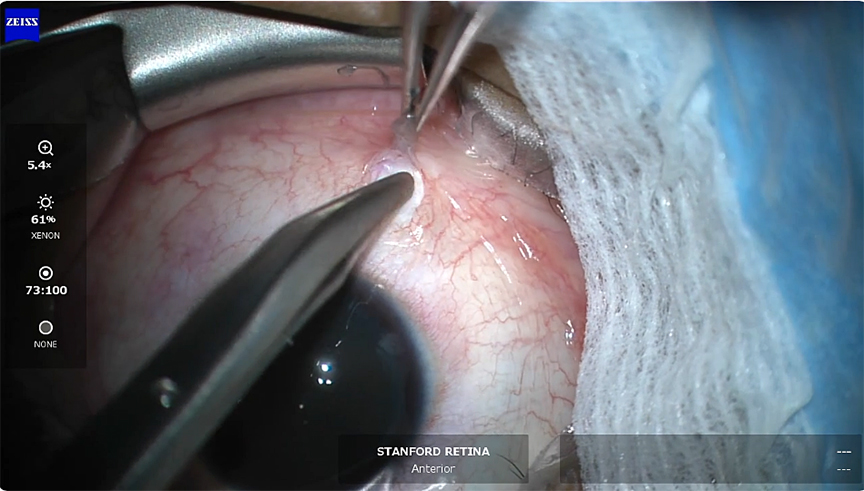

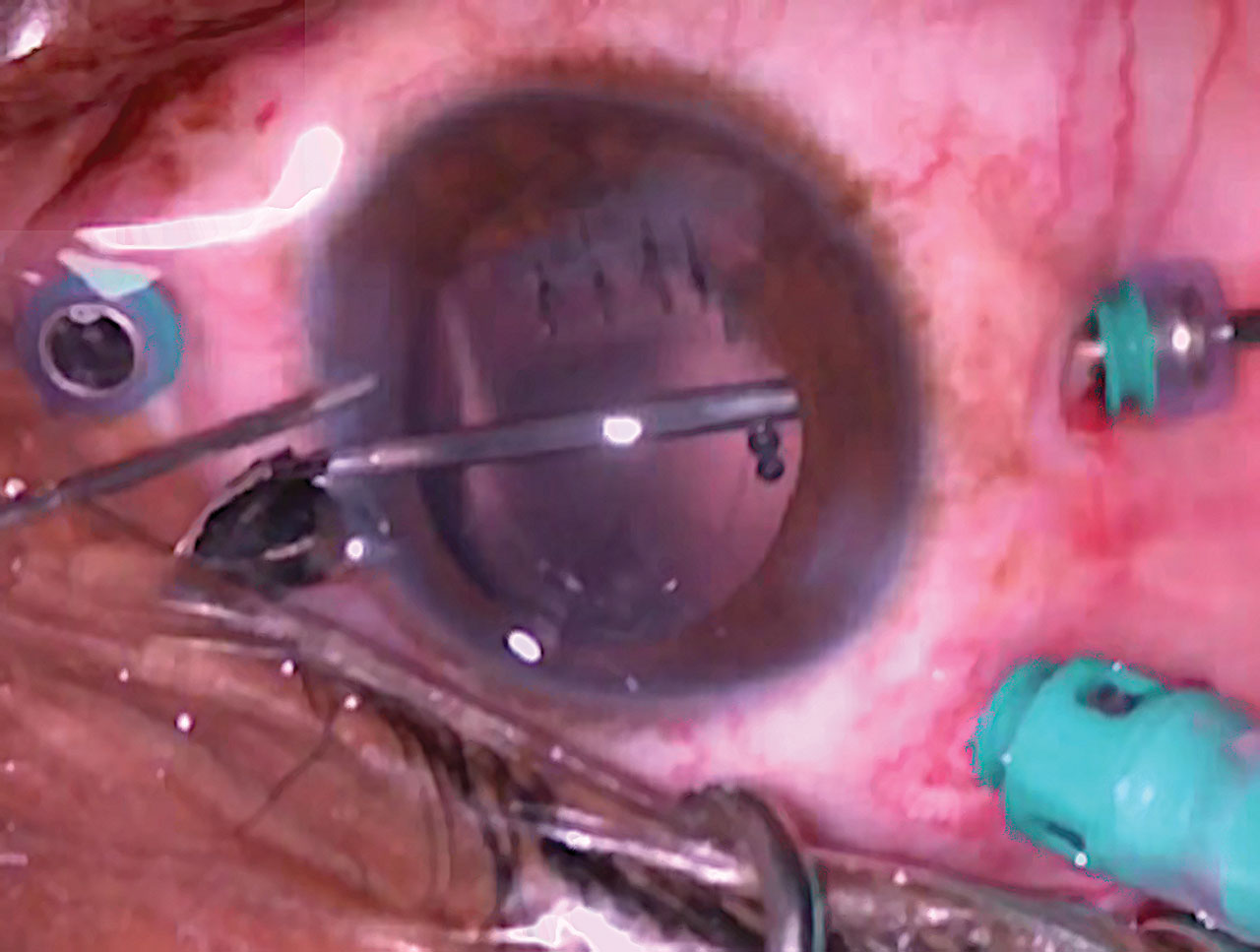

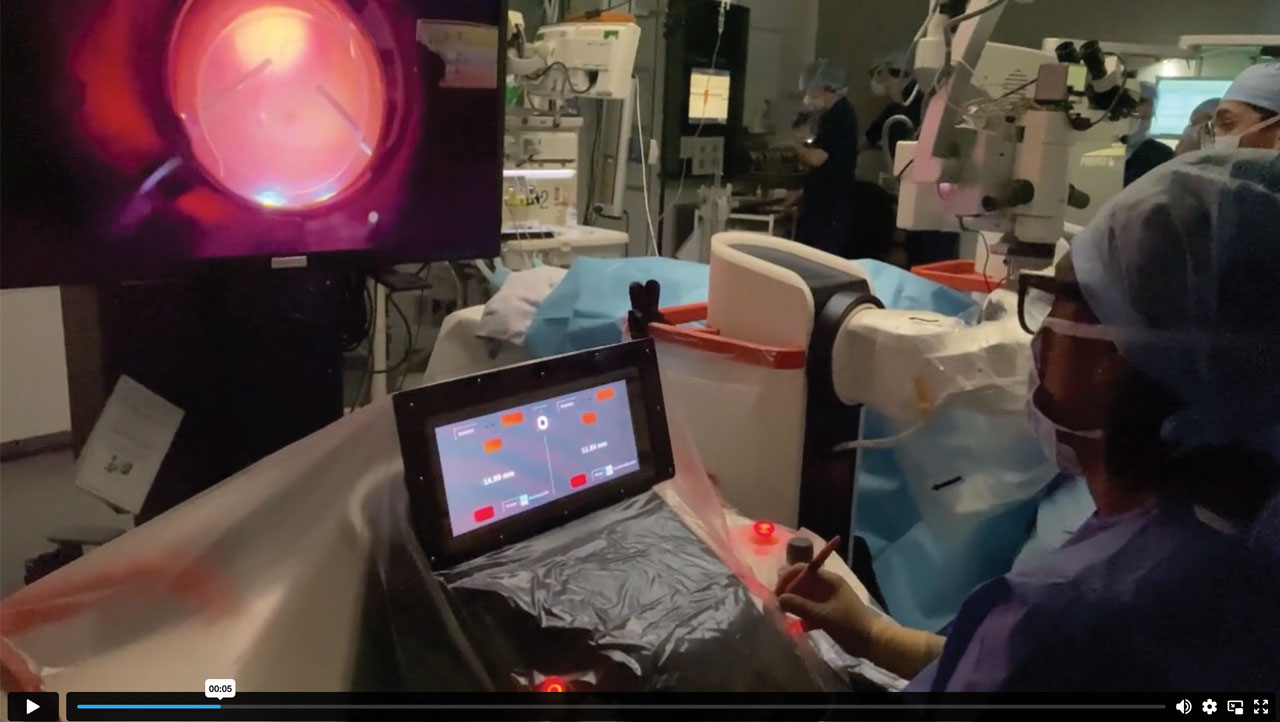

During surgery, I initially mark then utilize 27-gauge trocars to create the scleral tunnels through which I will externalize the haptics. I like to use a 23-gauge platform for all lens cases. The patient had a previous thorough vitrectomy for retinal detachment repair. There, you can see the dislocated intraocular lens in the vitreous cavity. Here, I am removing any capsular remnants, and then aspirating the dislocated lens to visualize it anteriorly. Here, I’ll grab the lens with the 23-gauge MaxGrip forceps and use the vitrector to remove Soemmering’s ring and any capsular remnants, and then bring the intraocular lens into the anterior chamber. Then, I'll remove any remnants of the Soemmering’s ring that fell posteriorly. We have to be very cautious aspirating small remnants so as not to touch the retina. I create the clear corneal incision superiorly, inject viscoelastic agent into the anterior chamber, and remove the intraocular lens through a Pac-man technique. I then inject the 3-piece intraocular lens, and use 27-gauge MaxGrip forceps to externalize the first haptic. I burn the tip of the haptic with low-temp cautery creating a small bulb. I'll repeat the same maneuver superiorly here. We have to be very cautious while externalizing haptics, as you can actually dislocate the haptic through the scleral tunnel if you pull too hard. Lastly, I create a small inferior peripheral iridectomy with the cutter, and go ahead and close up the corneal wound and all ports. I like to suture all of these cases just to ensure there’s no hypotony to ensure that the intraocular lens remains stable.

A couple of surgical pearls and how to avoid pitfalls in these cases - I’d love to talk a little bit about the utility of 23-gauge platform for these cases, how you approach these dislocated intraocular lens cases, and how to avoid IOL tilt and slippage of haptics through sclerotomy tunnels in these cases. Some people like to work more anteriorly versus posteriorly in lens cases, so it would be nice to see what everyone thinks.

Dr. Weng: First of all, a beautiful job, Suzie. You make that look effortless and you are seriously one of the best at these types of cases, so thank you for sharing. I’d love to hear from John and Ray—is the modified Yamane your go-to technique, as it has become for many of us in the retina community in the past few years, or do you prefer other secondary IOL techniques?

Dr. Miller: I also use the modified Yamane, as you showed really beautifully here. I also teach with the MaxGrip forceps because I think it’s the most reproducible as we’re learning these new techniques. I try to learn lots of different ways and I still consider other lenses to try just because we have had that rotisserie issue with these types of lenses.

As far as gauge, I do not typically use 23 unless I’m doing a PPL [pars plana lensectomy]. I think of these cases as either 3-port or 5-port. In this eye, I might have done a 3-port 27-gauge because you’ve already done a thorough vitrectomy for the retinal detachment, so I shouldn’t have too much intraocular vitrectomy to do. So ideally, I could just put the ports superonasal/inferotemporal and use the infusion line as one of my externalization haptic locations and then just grab the lens with the working supertemporal normal port (it looked like this was a right eye). I think that you did a beautiful job and I think the 5 ports [approach is] very reproducible. You maintain good view, you have a little bit more flexibility if you have trouble grasping one of the haptics because you still have your access to your lights when you’re going for that second haptic. It’s a beautiful surgery.

Dr. Gasparian: Especially with IOL explantation, I’ll often err on the side of using 23-gauge just because when it comes to explanting the lens itself, often times I feel as though I have more stability while grasping IOLs with 23-gauge MaxGrip forceps as opposed to a 25-gauge or a 27-gauge. That's just something I’ve picked up during training and have continued using in practice and have seen successful results with them.

Dr. Miller: Absolutely, great setup. I guess I'm cheating because I do use bigger instruments from our cataract colleagues throughout the corneal wound, so you can use the MST forceps or other things.

Dr. Iezzi: I thought it was a great job. I actually suture my lenses in with Gor-Tex. I use CZ-70, so it's a little different of a technique, and I do it with 27 gauge.

What I have found is that there are Soemmering’s rings and there are Soemmering’s rings. Sometimes you get these calcific bones that are encircling your lens. I try to avoid getting into vitrectomy removal of such rings. I’ll try to take it along with the IOL, if I can. I’ve even had situations where I’ll take the optic and then I'll kind of reserve the Soemmering’s ring in the angle to then take out as a separate entity. I really try to avoid vitrectomy in the Soemmering’s ring just because of the calcium that I’ve encountered in the past. I just don’t like getting surprised by the toughness of some of those things.

Dr. Miller: It can take longer to get that out than the IOL.

Dr. Iezzi: That's so true, and once you’re in that position, you just wish you weren't. I do use viscoelastic as a third hand. So when I bring up the IOL from the back with aspiration, I usually have visco in the AC and I sort of apply the lens to the visco. It's sort of like gluing it to the cornea, in a sense. Not that it’s touching the cornea, I just use it to give me a little bit of time to let go of the lens and then reformat, get the haptic into the AC. I find that to be a very helpful trick, using visco as sort of a glue to give me some stability as I position the haptics into the AC.

Dr. Gasparian: I’ve definitely been in that situation where the Soemmering’s rings can be very calcified. In those cases, I’ll take what I can get. If there are any remnants of it in the anterior chamber, I'll use the MaxGrip forceps to just gently pull it through the main corneal wound.

Dr. Weng: It’s really interesting that you mentioned that, Ray. I remember one I encountered a couple years ago that was so dense that I tried using the fragmatome to remove it and it still wouldn’t eat. It was like stone, just as you said. You're absolutely right that turning to the approach of removing these in a similar way to how you would an IOFB is very appropriate in certain cases.

Dr. Miller: I think if you can get it up towards your corneal wound, then you can use the fluidics of the infusion from the back to just to depress the back edge of your corneal incision and sort of burp everything out. That is the easiest way. I think along these lines, because of what Ray said, I do sometimes think about rescue. Could you talk a little bit, Suzie, around what are the parameters in which you would consider rescuing this lens, or a 3-piece, and what are your techniques for those different IOL situations?

Dr. Gasparian: I'll typically only rescue 3-piece IOLs. If it’s a single-piece IOL that's been dislocated, I'll explant those lenses and then insert a new 3-piece lens and fixate those haptics. Recently, I had a case of a dislocated lens—it was an MA60AC (Alcon) actually—and so that one, the haptics were intact, the lens was in good condition, so I was able to salvage that lens and was able to fixate the haptics nicely. That case went very well.

Dr. Miller: Did you clean off the capsule from that MA60? Are you pretty meticulous? Do you take some, or just clear the tip? What are your thoughts?

Dr. Gasparian: Actually, the lens itself didn't have any capsular remnants, no Soemmering’s rings, no issues there. However, for all cases I'll do a sulcus depression and make sure that I remove all of the capsular remnants because often if that stays there and fibroses down, you can see lens tilt. So, I always remove the capsular remnants even if it’s not actually encircling the lens itself. Any PMMA lens, of course, will be removed through a scleral tunnel, but any acrylic lens I’ll cut and remove.

Dr. Miller: I agree with your points. I just rescue sometimes, so if it’s a tough capsule and it’s a one-piece you can suture a proline through there like a belt loop technique if the capsule is sturdy around the haptic. That gives you enough to make sort of a radial 1 mm-2mm back prolene scleral suture lens.

Dr. Weng: A couple of really subtle points, Suzie, that you showcased nicely. I love that you emphasized cleaning up the capsule remnants at the sulcus. I think that’s an underappreciated maneuver that really does help with the final position of the IOL and avoiding some of the tilt that you can see. Another thing, too, is really where you’re starting. So not just making sure that you're exactly 180° apart when you mark the cornea through the limbus, but also the approach that you take with those cannulae. They really have to be as symmetric as possible, and that includes that approaching angle. So if you’re approaching one side at 30° and the other side at 45°, even if you tunnel the same length and are exactly 180° apart, you will end up with IOL rotation. It's not always the IOL’s fault! Appreciate you teaching us that subtle point—just a beautiful case, and we really appreciate you showing it. RP