Overview

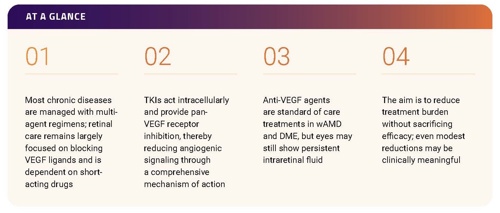

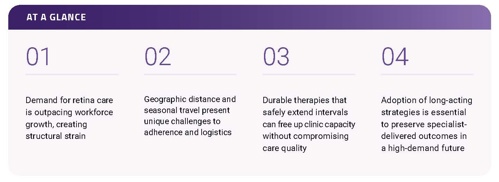

Durability remains a leading unmet need in wet age-related macular degeneration (wAMD) and diabetic macular edema (DME). Trials show that anti‑vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy can deliver substantial vision gains, but routine practice often underperforms because frequent dosing is challenging to sustain. Undertreatment, missed visits, and fluid variability contribute to long‑term vision loss relative to clinical trials, and loss to follow up is common in clinical practice.

Long‑acting tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) offer sustained delivery and a novel mechanism that may provide a practical path to reduce variability between visits while maintaining outcomes.

The Promise of Long-acting TKIs to Improve Long-term Outcomes in wAMD

Determinants of visit variance and eventual undertreatment

- Caregiver dependence

- Long travel distances

- Seasonal migration resulting in cross-practice care

- Prior authorization resets

- Hospitalizations

- Limited numbers of retina specialists

Durability Remains the Central Unmet Need in wAMD

Jayanth Sridhar, MD: In recent years, durability has been identified as a top unmet need in retina.1,2 Existing anti‑VEGF agents are highly effective, having helped shift wAMD from a blinding diagnosis to a manageable condition. Yet despite the FDA approval and success of multiple anti‑VEGF agents, real‑world outcomes still lag behind clinical trials,3 in part because patients receive fewer injections.4,5 The treatment burden required to sustain outcomes remains unsustainable for patients and clinicians alike. How should we be thinking about durability in terms of its priority for the retina community today?

Aleksandra V. Rachitskaya, MD, FASRS: The burden of treatment on patients, their caregivers, and our practices is tremendous. Undertreatment with anti‑VEGFs is a problem because patients struggle with transportation, caregiver strain, and competing responsibilities. Still, greater durability is only meaningful if it preserves anatomic control and vision: the bar for long‑acting agents is to achieve at least equivalent outcomes and maintain them over the long‑term while requiring fewer injections.

Shipla J. Desai, MD: Patient adherence tends to erode during long‑term maintenance rather than the induction phase of a treat‑and-extend regimen. Transportation remains a major barrier, especially for patients who depend on caregivers for travel, or who attempt to drive despite impaired vision.6 Patients with DME, often younger and balancing employment and family responsibilities, are especially vulnerable to loss‑to‑follow‑up, making durability particularly valuable for this group.

The maintenance stage of treatment is the challenge

Basil K. Williams Jr., MD: Important differences exist between patient populations in clinical trials and those seen in real‑world practice. In diabetes, trial participants often have better-controlled disease, which shapes outcomes differently than in broader patient populations carrying higher disease

burden. Treatment‑naïve patients also tend to respond more favorably than those with longstanding pathology.

High adherence in clinical trials is supported by an infrastructure of dedicated study coordinators, research staff, and sponsor oversight that helps maintain visit schedules. In contrast, retina clinics must contend with a wider set of real‑life barriers: patient illness, transportation challenges, and insurance hurdles. As a result, adherence tends to be lower, follow‑up can be less consistent, and undertreatment is more common outside of trial settings.

The Impact of Undertreatment

Sridhar: Post hoc analyses have demonstrated that eyes with the greatest retinal thickness variability are most likely to develop fibrosis and atrophy over time. In CATT and IVAN, patients in the highest quartile of fluctuation had significantly worse long‑term visual outcomes compared with those in the most stable quartile.7–9 More recent analyses of HAWK and HARRIER similarly showed that greater fluctuations in retinal thickness were associated with worse visual outcomes and higher rates of fibrosis.10 Real-world datasets confirm these findings, linking greater variation in retinal thickness with higher risk of fibrosis and vision loss.11

In clinical practice, retinal fluid fluctuations are seldom monitored longitudinally; clinicians typically compare only the most recent optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging rather than tracking variability across years, limiting recognition of the cumulative impact of instability on long‑term outcomes. These observations raise a key clinical question: is fibrosis inevitable in chronic wAMD, or is it concentrated in patients with more aggressive disease or suboptimal control due to real‑world constraints on visit intervals?

Williams: wAMD and diabetic eye disease are heterogenous and multifactorial, involving complex biological processes driven by angiogenesis, inflammation, and fibrosis.12 Regardless of agent, however, many patients exhibit the familiar sawtooth pattern of fluid recurrence. More consistent, sustained delivery would help smooth those fluctuations.

Priya S. Vakharia MD, FASRS: Long-acting TKIs may help reshape how fluid is interpreted in clinic. The younger generation of retina specialists is already becoming more tolerant of small levels of subretinal fluid, recognizing that not all fluid is harmful and some resolves on its own. Having a long‑acting treatment onboard could allow clinicians to adopt a more measured approach, giving extra confidence to monitor very small levels of subretinal fluid.

Sridhar: There is also a growing distinction between the presence of fluid and the variability of fluid. Emerging data suggest that some patients do well with stable, low levels of subretinal fluid,13 while outcomes are poorer when fluid fluctuates dramatically between visits.11 These shifts may be more than just anatomical changes, they could represent underlying cellular processes.12 Differentiating between stable and variable fluid may help refine treatment strategies in the era of long‑acting therapies.

Why Fewer Injections Matter for Patients

Avni P. Finn, MD, MBA, FASRS: Intravitreal (IVT) drug delivery has improved over time. Patients who remember the early days of anti‑VEGF injections often comment on how much more comfortable today’s injections are. Despite these advances, some patients still require dosing every four weeks, regardless of the agent used, and others demonstrate only partial fluid resolution despite multiple therapies. This is particularly true in DME, where chronic intraretinal fluid and hyper-reflective foci can persist.15

Rachitskaya: Even with improvements in technique, many patients continue to dread IVT injections.16 Anxiety is common, and some describe the experience as something they tolerate rather than accept, noting that recovery can take a full day and limit normal activities. Reducing the frequency of injections would ease that burden and improve quality of life. While the procedure is extremely safe overall, each injection still carries a small but serious risk of complications such as endophthalmitis.17,18 Cumulatively, higher numbers of injections increase that exposure. Longer‑acting therapies therefore hold value not only for convenience, but also for safety and patient experience.

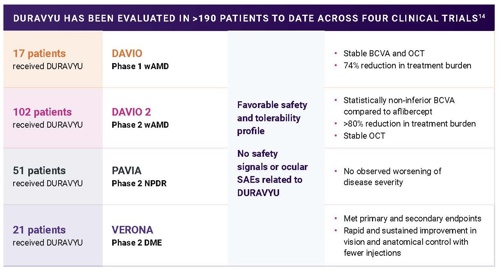

Supported by the largest intravitreal TKI clinical trial program, DURAVYU™ (vorolanib intravitreal insert; investigational) has been evaluated in over 190 participants, and is currently being studied in two phase 3 studies with over 800 participants. In DAVIO 2, the majority of DURAVYU‑treated eyes were supplement‑free for 6 months with a single dose. The phase 3 LUGANO and LUCIA trials programs are now underway to evaluate whether the efficacy and safety observed in earlier studies can be reproduced in larger populations with wAMD

BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; CST, central subfield thickness; DME, diabetic macular edema; NPDR, non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy; OCT, optical coherence tomography; SAE, significant adverse event; wAMD, wet age-related macular degeneration

Vakharia: Patient noncompliance is often underestimated. Chart reviews reveal that some patients believed to be taking only short breaks in fact return to clinic much later.19 The most noncompliant patients don’t come back to see us at all. The gap between expected and actual adherence underscores the importance of therapies that maintain disease control even when visits are missed.

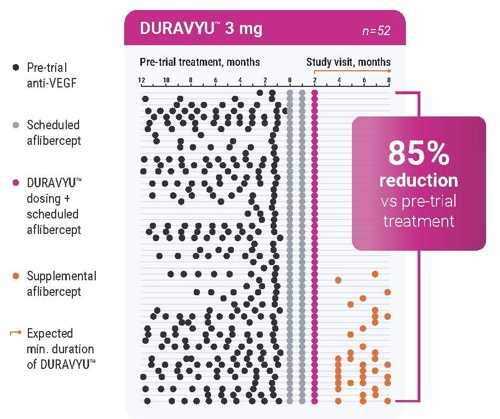

The majority of eyes treated with DURAVYU were supplement‑free up to Month 8. Participants receiving DURAVYU experienced approximately an 80% reduction in treatment burden relative to their pre‑trial treatment.20 These findings indicate that sustained‑release TKIs have potential to achieve clinically relevant reductions in injection burden without compromising efficacy.

In DAVIO 2, DURAVYU 3 mg reduced treatment burden by 85% compared to the prior 6 months (annualized mean of 10 anti-VEGF injections before the trial for both arms)20

Finn: Many elderly patients with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or other comorbidities may be hospitalized for long periods of time. During those interruptions, retina care could be deferred for months at a time. Patients frequently express regret over missed injections and the vision loss that can occur while they are away. A therapy that continues to work during these unavoidable gaps would be invaluable, ensuring stability even when regular visits are impossible. The path forward for TKIs will depend on proving safety and efficacy, which are fundamental to any new therapy. Early trial data suggest they can meet this standard, and their greatest promise lies in combination approaches that build on current treatments and add new layers to wAMD and DME treatment paradigms.

Beyond Monotherapy: The Case for a Multi-modal Future in Retinal Disease

Barriers and Enablers of Combination Use

Vakharia: Newly diagnosed patients with wAMD or DME often want clarity about their management plan: how many injections will be needed, how frequently visits will occur, and what the long‑term commitment looks like. In reality, the answer is usually uncertain: therapy is initiated, then extended as tolerated, with no set timeline. This lack of predictability leaves many patients confused and unsettled. Long‑acting therapies could help restore a sense of structure, offering a defined framework that makes the treatment journey feel more transparent and manageable.

Long-acting therapies are going to change the way we practice

Rachitskaya: A common question from patients is whether treatment will continue forever. While current therapy is effective now, the treatment landscape is evolving and future options may look different. Framing care this way can actually support adherence, as patients recognize that novel mechanisms are on the horizon and that treatment will not always mean coming in frequently. The prospect of longer‑acting approaches provides reassurance that the burden of care will lessen over time.

Vakharia: Community retina specialists often face the mental burden of integrating one agent or another, and the lack of an algorithm adds to the uncertainty. The appeal of TKIs lies partly in their potential to create structure: a foundation injection every six months, with the option to supplement with an anti‑VEGF as needed. Such an approach could standardize decision‑making, reduce variability, and make multimodal regimens more practical. Without that clarity, many clinicians remain reluctant to adopt combination therapy despite its theoretical benefits.

Finn: Practical barriers must also be factored in when considering the potential uptake of combination therapy. Discussing treatment changes requires time in already crowded clinics, and integrating multimodal regimens adds complexity to workflows. Insurance hurdles compound the challenge. Authorizations may exist for one agent but not another, and some payers may not permit dual approvals, making it difficult to combine treatments or move fluidly between them.

Williams: Practical questions also surround how TKIs will be integrated with insurance plans. Many payers require patients to begin with bevacizumab for loading before moving to higher‑cost agents. If a TKI is used for that initial regimen, it is unclear how insurers will handle subsequent transitions, particularly if patients show strong response to the combination of bevacizumab and a TKI. Whether coverage will allow a switch to another anti-VEGF will be an open question, highlighting the need for clarity on how long-acting therapies will fit within existing authorization frameworks.

Brian K. Do, ND, FASRS: The transition from bevacizumab to aflibercept illustrates how treatment baselines have shifted over time. Looking forward, the field may continue moving in this direction of using the most effective and durable options as early as possible when access allows.

Williams: Patient communication also plays a role: introducing a second IVT therapy can be difficult to frame as an enhancement rather than a sign that the first drug failed. Starting the conversation earlier can make patients less resistant. When treatment options are presented only at the moment of change, the discussion becomes heavy and disruptive. If patients hear from the beginning that therapy might evolve, it softens the transition. Framing future possibilities early helps spread the conversation into smaller steps, reducing the burden of consent and making it easier to adjust therapy over time.

Rachitskaya: The treat‑and‑extend model works well in practice because it gives both physicians and patients a clear, predictable plan, even if it may not be sustainable long‑term. Combination therapy disrupts that familiarity, requiring clinicians to rethink how the roadmap is presented and how it is organized mentally. Clinical trials will be critical in shaping this new conversation. Will the plan involve loading doses followed by a long-acting agent, with fixed follow-up intervals? Will it rely on home OCT‑guided monitoring to trigger supplemental treatment? These questions remain unanswered. Unlike dexamethasone implants, which are often introduced following suboptimal response to initial treatment, combination therapy with emerging agents may need to be discussed from the very beginning.

Williams: Trial design around TKIs has already begun to shift the treatment mindset. Physicians no longer approach these agents as a switch but rather as a foundation that can be supplemented with anti‑VEGF when needed. This framing moves combination therapy into the conversation from the very beginning, instead of introducing it only after an incomplete response. Even so, clarity is still required around when to add therapy, how to structure follow‑up, and what the overall plan should look like.

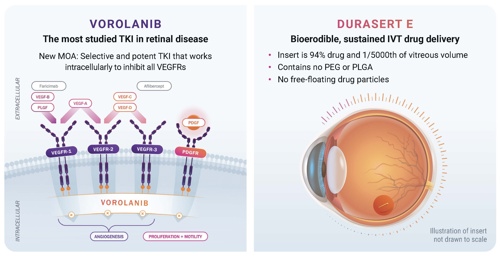

TKIs offer a different and unique mechanism of action: comprehensive blockade of VEGF‑R1, R2, and R3, and platelet‑derived growth factor (PDGF), irrespective of VEGF. Acting intracellularly, they inhibit multiple signaling pathways involved in angiogenesis. One TKI, vorolanib, has also demonstrated it binds to JAK1, inhibiting IL-6-mediated inflammation. Unlike anti-VEGFs, which neutralize extracellular VEGF-A, TKIs act inside the cell to inhibit multiple angiogenic signaling pathways. Vorolanib is a potent and highly selective TKI that continuously blocks all isoforms of VEGF above IC50 for at least 6 months. Preclinical animal data suggest that vorolanib may have neuroprotective properties, and its inhibition of PDGF could offer antifibrotic benefits. Vorolanib does not inhibit TIE-2, which is crucial for vascular stabilization.

AAV, adeno‑associated virus; IVT, intravitreal; MOA, mechanism of action; PDGF(R), platelet‑derived growth factor (receptor); PEG, polyethylene glycol; PLGA, poly lactic‑co‑glycolic acid; PLGF, placental growth factor; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VEGF(R), vascular endothelial growth factor (receptor)

Vakharia: Long‑acting therapies are poised to reshape retina care. Not every patient will move from four‑week dosing to six‑month intervals, but most stand to gain meaningful relief from treatment burden. These agents will not eliminate injections entirely, yet they promise to streamline practice flow while giving patients greater predictability and independence. A true advance lies in therapies that both ease the burden of care and sustain durable outcomes, even if supplemental dosing remains necessary. Lowering cumulative exposure to frequent injections, even incrementally, offers clear benefits for adherence, patient experience, and long‑term safety.

From Monotherapy to a Combination Framework

Sridhar: In many chronic diseases, management relies on multi‑agent regimens that balance long‑ and short‑acting therapies. Within ophthalmology, glaucoma treatment commonly combines prostaglandin analogs, beta-blockers, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. By contrast, management of wAMD has remained largely VEGF‑centric and dependent on relatively short‑acting monoclonal antibodies. There was a time when no treatments were available at all, making the landscape’s rapid evolution striking. Yet this reliance on a single pathway may impose a therapeutic ceiling.4

Do: For DME in particular, many clinicians are now hesitant to rely on anti‑VEGF monotherapy alone. Corticosteroids are often considered earlier, with some moving to dexamethasone or fluocinolone implants when response is incomplete after a few anti-VEGF injections. This reflects the complex and not yet fully defined molecular pathways underlying the disease. Current regimens likely do not address all drivers of pathology, and future therapies may target broader cytokine networks. The goal will be to deliver medications that act on multiple pathways with minimal ocular risk, enabling more complete and durable control. TKIs’ broader mechanism combined with sustained‑release drug delivery could lead to more consistent fluid control, less variability between visits, and reduced reliance on short‑acting monotherapy.

Williams: The term “switch” became ingrained in the retina vernacular, leading many clinicians to think in binary terms rather than considering combination therapy. For DME in particular, dual therapy with anti‑VEGF and steroids may benefit patients with mixed-mechanism disease, especially those with a strong inflammatory component.

Finn: Using multiple mechanisms could move the field beyond reliance on a single pathway and reshape practice paradigms, offering clinicians the ability to build regimens that are more durable, more flexible, and more aligned with the complexity of retinal disease. Even with the emergence of second‑generation anti‑VEGFs, a subset of eyes have persistent exudation despite regular VEGF‑A suppression. Despite the success of anti‑VEGF agents, retinal disease may be only partially controlled, leaving persistent intraretinal fluid.15

Rachitskaya: There is excitement around agents with completely new mechanisms of action, particularly those targeting intracellular pathways. Their uniqueness lies in offering something fundamentally different from traditional anti‑VEGF therapy. Key questions remain, especially regarding how these drugs will integrate into existing treatment paradigms. Upcoming phase 3 trials are expected to clarify their role, providing guidance on how to combine or sequence them within current practice.

How Long-acting Therapies Can Help Bridge the Retina Specialist Workforce Gap

Rising Demands in Exudative Disease

Sridhar: Demand for eyecare continues to rise with an aging population. The ratio of specialists to patients is already strained, and the imbalance will only worsen over the next decade.21 Retina is among the least well-equipped fields in medicine in terms of provider density.22 These realities highlight the urgent need for therapies that may extend treatment intervals and reduce visit frequency.

Desai: There is also a clear geographic imbalance in access to retina care. Within cities, specialists are concentrated and clinics remain busy, yet many physicians still travel long distances to reach satellite sites. Patients often do the same, driving several hours each way for an injection visit that consumes an entire day. In these situations, the limiting factor is not time off work but the burden of travel itself. Durable treatment options could ease that strain by reducing the number of long trips required, making care more feasible for those living farther from specialty centers.

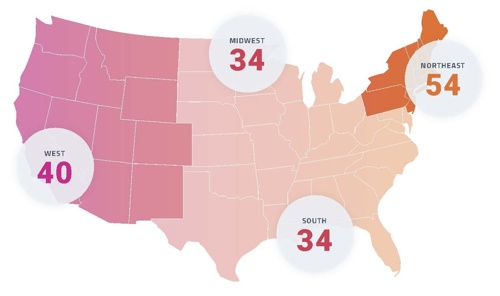

Retina may continue to rank among the least supplied surgical subspecialties relative to patient need. Regional disparities are evident, with the Northeast showing the highest concentration of retina specialists, and the South and Midwest showing the lowest. Note: Hawaii and Alaska are included in the West region.22

Finn: Access to care remains one of the central challenges in retina practice. The field continues to debate whether that gap should be addressed by reshaping the workforce or by expanding the pool of providers who deliver injections. Many clinicians, however, believe that preserving high‑quality, physician‑led care is critical. More durable treatments support that goal by reducing visit frequency while maintaining outcomes. Retina also stands apart within medicine; few other specialties require physicians to drive regularly to multiple satellite clinics. This structure, common to both academic and private practice settings, reflects the effort to extend specialty care to patients living far from major centers.

Sridhar: Retina is unusual among medical specialties in that clinicians remain closely connected across the country, largely because of snowbird patients. Seasonal migration creates a network of colleagues and friendships, but it also produces major operational challenges. Patient volumes fluctuate unpredictably between winter and summer, forcing practices with full‑time staff to absorb seasonal surges and lulls. More durable treatment options could help smooth those swings by reducing the number of visits during peak migration periods.

Nearly 2/3 of eyecare providers and clinic staff in a large, multi-national survey reported clinical capacity constraints that limit their ability to deliver optimal care23

Rachitskaya: The workforce challenge is deeply complex and extends beyond retina alone. Practice patterns in the US and abroad highlight systemic issues that affect not only daily care delivery but also advocacy across ophthalmology as a whole. Another dimension is recruitment: how sustainable does the field appear from the outside? The perception of long hours, extensive travel, and unrelenting procedural demand could discourage residents from entering the specialty. Without attention to these dynamics, the imbalance between patient need and physician capacity will only intensify. Long‑acting therapies are not a complete solution, but they offer one concrete step toward reducing workload and making the field more sustainable over the long term.

Practice Realities Across Regions

Williams: Prior authorizations can be another hurdle: patients may have prior approval at one practice, but that coverage does not always transfer when they move or seek care elsewhere. After waiting months for an appointment, they may arrive only to be told treatment cannot proceed, forcing another delay. For those who travel long distances, the impact is especially burdensome. The goal is to deliver treatment when the patient is in the office, not to send them home without care because of administrative gaps.

Sridhar: Beyond insurance hurdles, practical issues such as medication storage and inventory management add to the complexity of care. Agents that are shelf‑stable offer a clear advantage, especially as the number of available therapies grows. The challenge is not only choosing the right treatment for the patient but also managing practice logistics, inventory, and distribution supply across satellite offices. Longer-acting and more stable formulations simplify these demands, making integration into diverse practice settings more feasible.

Vakharia: Shelf stability is critical, particularly in regions prone to power outages such as Florida. During hurricane season, practices often operate with minimal inventory because of the risk of losing refrigerated medications if electricity is interrupted. The ability to store agents without constant temperature control provides enormous value, protecting against supply loss and ensuring continuity of care. From a practice management standpoint, stability is not just a convenience. It is a necessity.

Sustaining the Future of Retina Care

Vakharia: Retina specialists may wonder how long‑acting therapies will affect practice

economics. TKIs appear well suited to integrate without disruption, given that patients may feasibly be anchored with a TKI every six months with supplemental anti‑VEGFs as needed, which should avoid a dramatic change in workflow.

Sridhar: Burnout is a growing concern as retina volumes rise year after year. The constant pace of moving from room to room, managing complex conversations, and juggling both clinic and surgical responsibilities takes a cumulative toll. Even outside the busiest seasons, many practices already operate at capacity, and surges exacerbate the strain. Layered on top are clinical trial commitments and a growing population of patients requiring ongoing injections for decades.

At the same time, burnout is tied to culture as much as workload. Retina specialists often struggle to set boundaries because the instinct to help patients is strong. Overbooked schedules are common, and physicians routinely squeeze in additional patients, especially for those on strict intervals, because turning them away feels unthinkable. This generosity sustains patient care but also takes a toll when repeated day after day.

With limited ability to expand the physician workforce, the question becomes how practices can sustain increasing volumes without compromising care or clinician well‑being. Long-acting therapies provide one avenue of relief, easing appointment density and reducing the relentless cycle that drives stress and burnout.

With workforce growth lagging behind patient demand, more durable therapies will become essential to sustain delivery of care

Vakharia: There is a limit to how much volume a practice can absorb. Growth comes from delivering care patients value, not simply adding more visits. If the specialty does not find ways to accommodate treatment burden, others will fill the gap, even if they are not retina specialists. Protecting the field means ensuring patients have access to high‑quality, retina‑led care while also making workloads sustainable.

Finn: When we consider the reasons we initially chose retina as a career, many of us valued the diversity in the subspecialty from surgery to clinic‑based procedures and the opportunity to build longitudinal relationships. That balance has recently shifted to much of our time spent in clinic due to the high demand and number of injections; more durable therapies may shift the pendulum back to a more balanced practice model.

Vakharia: Ultimately, the priority remains patient vision. Every decision in the clinic or operating room is driven by the goal of improving outcomes, whether that means refining surgical techniques or carefully adjusting treatment regimens. Yet it is still too early to know how new long‑acting therapies will perform outside of trials; post‑marketing experience will be essential.

From Burden to Breakthrough

Sridhar: Current therapies have transformed outcomes, allowing patients to see better than ever before, but they have also created new logistical, systemic, and workforce‑related challenges. The task ahead is to ensure those challenges do not leave patients behind. Long‑term vision outcomes highlight the importance of thinking beyond the first year or two of treatment. And while early gains are meaningful, the true measure of success is sustaining vision over decades.

Emerging long‑acting therapies offer the potential to address the very gaps that weigh most heavily on patients and practices. By easing treatment burden, reducing risk from missed visits, and broadening therapeutic mechanisms, these innovations may help protect vision more reliably across the long arc of chronic retinal disease.

Williams: It is an exciting time for retina. TKIs are on the horizon, with gene therapies and other targeted agents not far behind. As our understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms deepens and adjunct monitoring tools like remote OCT monitoring become more widely used, the therapeutic landscape will continue to expand. The challenge will be marrying these scientific advances with the practical realities of daily practice—integrating new options in ways that improve outcomes while remaining feasible in busy clinics.

Do: Looking decades ahead, it may be hard to imagine that treatment once centered on a single pathway—and only through one mechanism of action to influence it. The expectation is that retina will evolve into a field defined by multiple mechanisms and durable approaches, supported by a workforce that grows with it. Bringing more trainees into the specialty will be essential, ensuring that advances in science translate into sustained access for patients.

What is clear is that the future will hold more mechanisms, more durable approaches, and possibilities that today seem almost unimaginable

Desai: Innovation has always defined retina. In just the past decade, new options have reshaped expectations, and the next generation of therapies promises to do the

same. Keeping pace with these developments ensures that patients continue to receive the best possible care.

Vakharia: For patients who once heard there was nothing available, the outlook is shifting. Advances in artificial intelligence and long-acting delivery make it increasingly difficult to predict where the field will be in 20 or 30 years.

Disclaimer: DURAVYU™ has been conditionally accepted by the US FDA as the proprietary name for EYP‑1901 (vorolanib intravitreal insert). EYP‑1901 is an investigational medical product and is not authorized for sale in any country at the time of this publication. FDA aproval in US and Marketingn Authorization in any other country and the timeline for potential authorization is unknown.

References

- Hahn P, ed. ASRS 2023 Preferences and Trends Membership Survey. Chicago, IL. American Society of Retina Specialists; 2023.

- Hahn P, ed. ASRS 2025 Preferences and Trends Membership Survey. Chicago, IL. American Society of Retina Specialists; 2025.

- Khurana RN, Li C, Lum F. Loss to follow-up in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration treated with anti-VEGF therapy in the United States in the IRIS® Registry. Ophthalmology. 2023;130(7):672-683.

- Holz FG, Tadayoni R, Beatty S, et al. Multi-country real-life experience of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for wet age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(2):220-226.

- Ciulla TA, Bracha P, Pollack J, Williams DF. Real-world outcomes of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in diabetic macular edema in the United States. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018;2(12):1179-1187.

- Card KR, Gordon GM, Carron R, Winthrop M, Bagheri N, Pieramici DJ. transportation issues among patients receiving intravitreal injections at a retinal specialist clinic (BURDEN Study). Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5(10):1052-1053.

- Rofagha S, Bhisitkul RB, Boyer DS, Sadda SR, Zhang K; SEVEN-UP Study Group. Seven-year outcomes in ranibizumab-treated patients in ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON: a multicenter cohort study (SEVEN-UP). Ophthalmology. 2013;120(11):2292-2299.

- Peden MC, Suñer IJ, Hammer ME, Grizzard WS. Long-term outcomes in eyes receiving fixed-interval dosing of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents for wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(4):803-808.

- Chakravarthy U, Harding SP, Rogers CA, et al. Alternative treatments to inhibit VEGF in age-related choroidal neovascularisation (IVAN): 2-year results. Lancet. 2013;381(9877):1258-1267.

- Sadda SR, Sarraf D, Khanani AM, et al. Comparative assessment of subretinal hyperreflective material fluctuations and vision outcomes in HAWK and HARRIER. Br J Ophthalmol. 2024;108(6):852-858.

- Evans RN, Reeves BC, Maguire MG, et al. Associations of variation in retinal thickness with visual acuity outcomes in neovascular AMD. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(10):1043-1051.

- Vujosevic S, Lupidi M, Donati S, Astarita C, Gallinaro V, Pilotto E. Role of inflammation in diabetic macular edema and neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 2024;69(6):870-881.

- Guymer RH, Markey CM, McAllister IL, et al. Subretinal fluid in neovascular age-related macular degeneration treated with ranibizumab using a treat-and-extend regimen: FLUID Study 24-month results. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(5):723-734.

- Data on File. EyePoint Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

- Bressler NM, Beaulieu WT, Glassman AR, et al. Persistent macular thickening following intravitreous aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for central-involved diabetic macular edema with vision impairment: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(3):257-269.

- Yiallouridou C, Acton JH, Banerjee S, Waterman H, Wood A. Pain related to intravitreal injections for age-related macular degeneration: a qualitative study of the perspectives of patients and practitioners. BMJ Open. 2023;13(8):e069625.

- Merani R, Hunyor AP. Endophthalmitis following intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injection: a comprehensive review. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2015;1:9.

- Falavarjani KG, Nguyen QD. Adverse events and complications associated with intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents: a review of literature. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(7):787-794.

- Obeid A, Gao X, Ali FS, et al. Loss to follow-up among patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration who received intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(11):1251-1259.

- Singer M, Ribeiro R. DAVIO 2 trial results: Assessment of treatment burden in wet age-related macular degeneration treated with EYP-1901 (vorolanib intravitreal insert) versus aflibercept. Presented at: Macula Society Annual Meeting; February 12–15, 2025; Charlotte Harbor, FL.

- Berkowitz ST, Finn AP, Parikh R, Kuriyan AE, Patel S. Ophthalmology workforce projections in the United States, 2020 to 2035. Ophthalmology. 2024;131(2):133-139.

- Ahmed A, Ali M, Dun C, Cai CX, Makary MA, Woreta FA. Geographic distribution of US ophthalmic surgical subspecialists. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2025;143(2):117-124.

- Loewenstein A, Sylvanowicz M, Amoaku WM, et al. Global insights from patients, providers, and staff on challenges and solutions in managing neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol Ther. 2025;14(1):211-228.

© 2025 EYEPOINT PHARMACEUTICALS INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.