This video was part of a roundtable discussion involving surgeons Christina Y. Weng, MD, MBA; John B. Miller, MD; Raymond Iezzi Jr, MD; and Suzie A. Gasparian, MD. An edited transcript of the case presentation and discussion follows below:

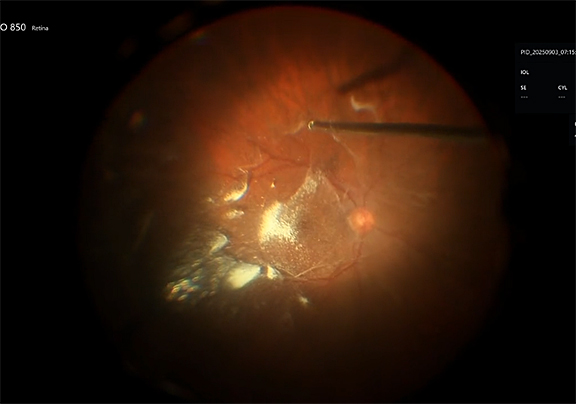

John B. Miller, MD: Thanks a lot for the invitation to show a case today. I’ll be showing how we’ve managed a complication that we all dread and hate to see after retinal detachment surgery. This is a 52-year-old male who presented after having a successful repair of a giant retinal tear (GRT) retinal detachment. It was a superotemporal tear and you can see in this OCT a tremendous number of subretinal perfluoro-octane (PFO) bubbles, including some right at the fovea. We’ll talk later in the discussion about how to avoid subretinal PFO. With that, I'll play the video.

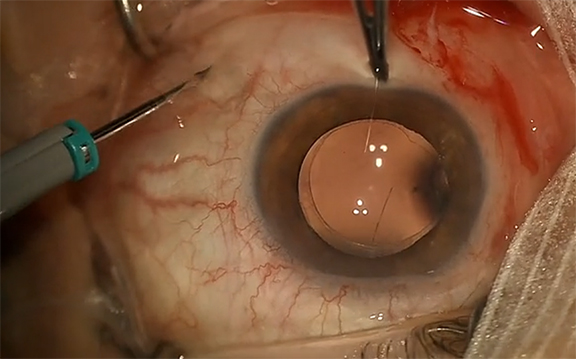

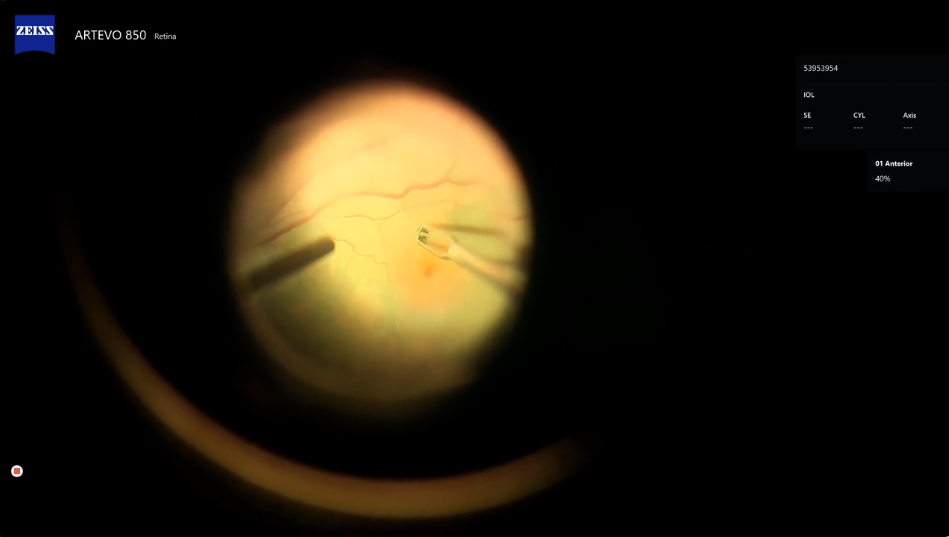

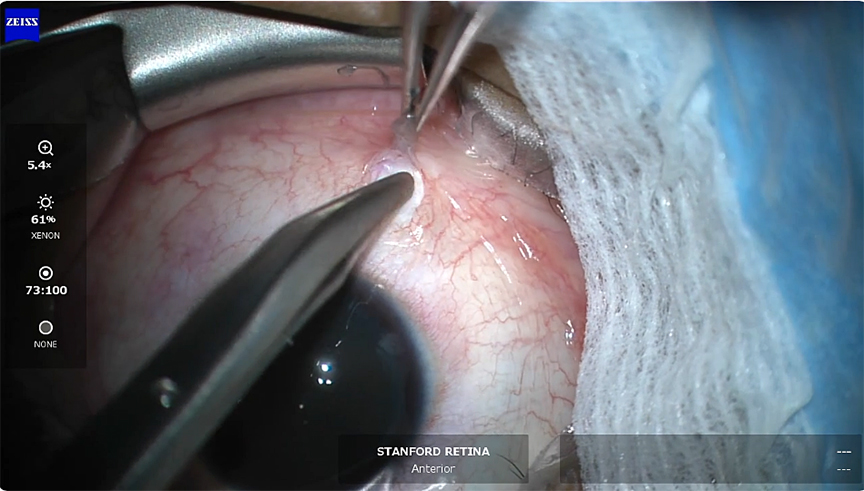

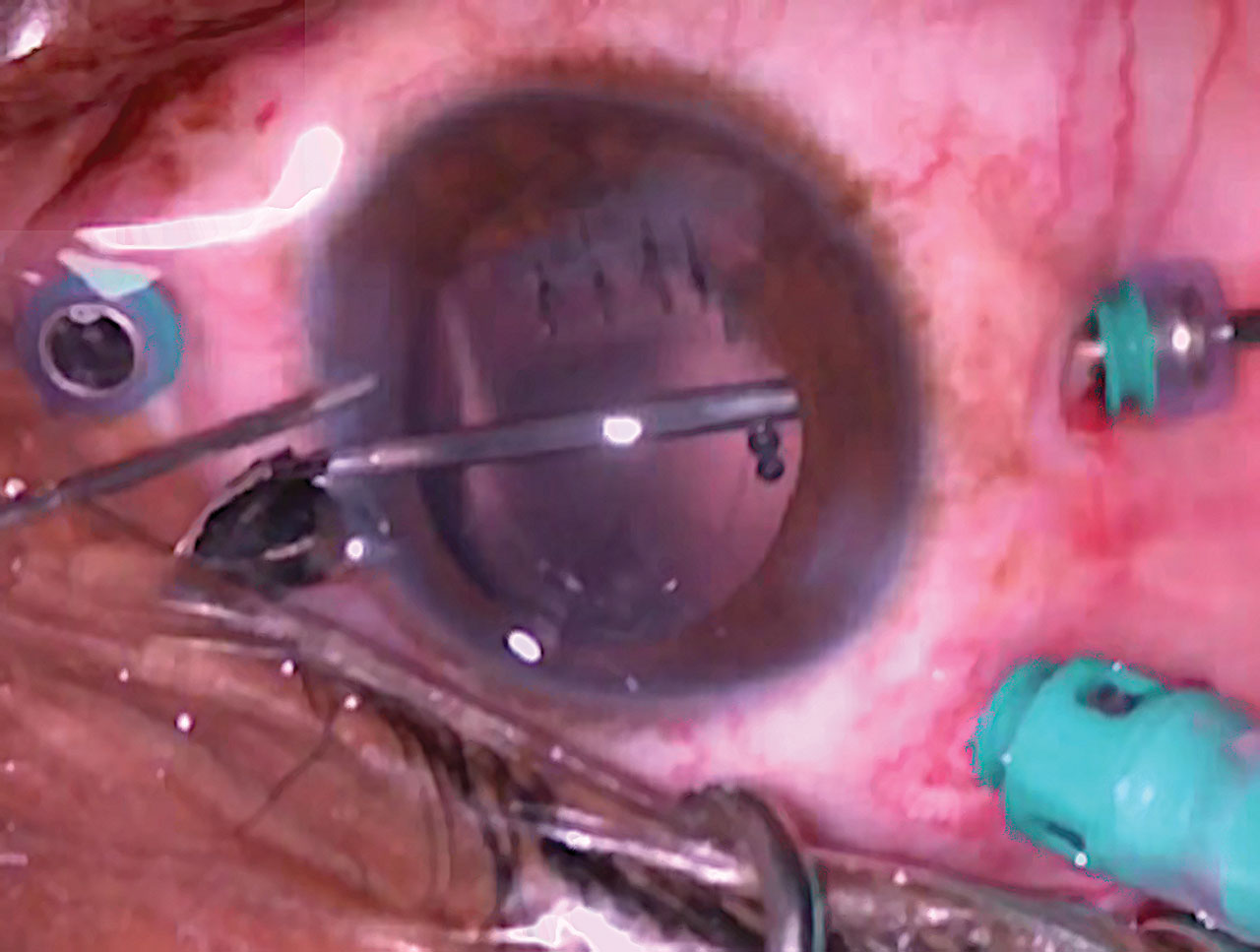

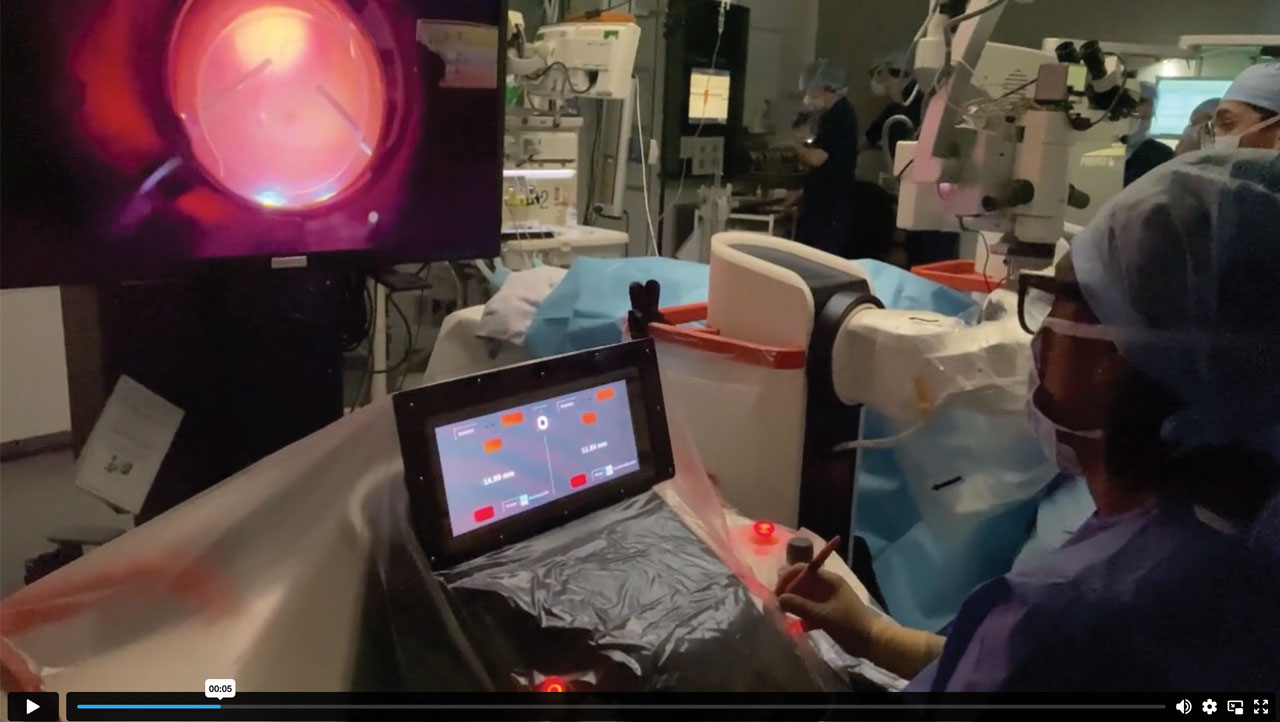

This patient at this point was post-vitrectomy a few months out . He had a significant cataract that was going to obscure our view for these delicate macular procedures, so we removed the cataract and placed the regular standard IOL. We can see this diffuse collection of PFO bubbles. We used the VFC injector and a subretinal cannula here to create a subretinal bleb. It’s important to have nice settings on your VFC, you want to try to have about 4 to 6 on the pressure, much lower than we use for oil, just to get a nice steady stream.

Here you can see us making a nice bleb. We're kind of starting in the superior macula. We don't want to be too close to the fovea, this is thin tissue. We tried to balloon the bleb up high enough to encompass all the subretinal PFO bubbles. I’m intentionally trying to create a lot of turbulence in the eye by running the vacuum at full throttle with the cutter. We saw a few bubbles come out, but not much. We’re now just aspirating here with the soft tip through a new retinotomy that we made. We've kind of dislodged them a little bit with that infusion washing, and we go through this cycle a few times: we get a few out, we re-bleb, the bleb keeps collapsing when we do that that aspiration with the extrusion. You can see a few of them actually coming out as we're re-blebing. The pressure of the re-bleb can push some of the PFO out here through it as well. Then we’re going to re-aspirate it and try to vacuum more out. After 2 or 3 of those rinses, we then use the surface tension of a larger PFO bubble to sort of squeegee the smaller PFO bubbles over towards the larger retinotomy. We also take advantage of that bigger bubble; hopefully, it would absorb the smaller bubbles if it could come in contact with it. We then went to a fluid-air exchange.

This is the postop OCT, where we can see good improvement in the number of PFO bubbles, but we certainly didn't get all the PFO bubbles. Some of that has to do with the time from the retinal detachment period to the time of our surgery. We did make a significant improvement for the patient. You can see some photoreceptor loss, but the patient did have an improvement in their visual acuity and they reported improved vision. This was a complex macula-off detachment, so a relatively good result for this surgical complication.

At this time, we can open it up to discussion with the group. Any thoughts on how to avoid subretinal PFO, and how to manage, and which PFO bubbles to go after? I think those are the 3 main questions that a retina fellow or a new faculty member would want to think about if they encountered this situation.

Dr. Weng: John, that was such a beautiful case, I appreciate you sharing that. I told you earlier that I had a similar nightmare situation with a superotemporal GRT in a young patient who suddenly bucked while he was under general anesthesia and ended up having a ton of these subretinal PFO bubbles creep in through the GRT and find their way to the macula as they tend to do. I personally don't use PFO all that much, for this very reason, but I do for GRTs. Because PFO has such a low surface tension, is optically clear, and has a low viscosity, it really is kind of the perfect storm for retention; some of the papers out there have cited up to 10% to 11% retention rate.

I would offer 1 tip to start off, which is something I always teach fellows and trainees about PFO: when you’re injecting PFO, you want to inject right into the bubble itself to help avoid creating fish eggs. I usually start right over the nerve and then I make sure that the tip of the cannula remains in that PFO bubble as it continues to grow. I’d love to hear tips from Ray and Suzie as well.

Dr. Iezzi: John, I think your outcome was fantastic. I really like your technique—I thought you were highly effective in getting those pesky bubbles out from under the retina. I think the secondary use of PFO to help coalesce them and to manipulate them was a great thought. A lot of times some form of external manipulation through the retina, either through a soft-tip cannula or perhaps even through a finesse loop, would allow you to coalesce those. I’ve found that there's a 40-gauge needle that has a beveled tip [MicroTip Beveled Cannula; MedOne Surgical]. It’s got a sharp tip, and we can insert it into these tiny little holes. So, I have a tendency of literally poking these individual bubbles. Of course, in this case there were a lot, and I don't know if it would have been possible to coalesce them, but I typically will insert this microneedle, which is sharp and beveled, into each of the cysts and aspirate and it does a really good job.

But certainly, I actually gave a lecture to the residents tonight and I said the best way to avoid subretinal PFO is to never use PFO [Laugh]. But of course, I think in GRTs it’s one of our main go-tos for a GRT. In my experience, when I get subretinal PFOs in a GRT, it's very much at the end. I think valved cannulas have been really helpful in reducing the intraocular turbulence that can emulsify this low-surface tension PFO. I kind of wish that PFO had a color so we could see it better, but I feel that a lot of the PFO emulsification happens at the end. I'm wondering if anyone else has any thoughts on that.

Dr. Weng: Those are great points, Ray, and I don't know that I have any additional insights, but I agree that valved cannulae have made a tremendous difference in preventing fish eggs from occurring. The other thing I do is turn down my infusion rate before placing PFO because even moving instruments in and out through valved cannulae can cause turbulence as well. Additionally, I scleral depress every single case before closing, but remember to do that before the PFO goes in if possible. If you must depress after PFO has been placed—which we sometimes need to do for lasering purposes—depress slowly and do not suddenly release as it can otherwise lead to bubbles forming.

I wanted to comment on one more thing, John. In my case, I also had a lot of small bubbles, but I had a large one in the central fovea area, and I was surprised—just as you beautifully showed in your video—that they didn’t just coalesce and come out with a subretinal bleb, which I had anticipated. They're sort of sticky; based on my reading, it seems like that’s even more so the case the closer you get to the fovea. For my patient with the large PFO bubble in the central fovea, I actually had to jostle the eye itself with a scleral depressor to be able to dislodge it and remove it through the retinotomy. That’s just another tip to share.

Dr. Miller: I mean I think the turbulence of the infusion both create but I was trying to use it to help to dislodge and I think that high flow you can try to create a rinse to free them from the undersurface of the retina. I agree with Ray’s point of using direct aspiration for one to three or five. This was certainly the most I’ve ever seen, and I would only go after them if they were in the central macula. I have seen PFO levels outside the arcade or at least in the mid-periphery, and those you can certainly leave. This was kind of the most extreme case and that's why we’re showing it at a rounds like this, because it kind of highlights a challenge that presented a different problem.

Dr. Weng: Beautifully managed. Suzie, you had a comment.

Dr. Gasparian: Just beautiful work. I think the key point in these cases if there is subretinal PFO is, ultimately, it's hard to get all of it out, so the focus should be on clearing the subfoveal area where the PFO is and if there is a little bit retained closer to the arcades, I don't think that’ll be as detrimental in terms of impacting the patient's vision. I like to keep the PFO as one large bubble and try to do as much laser as I can. Then, once I take the entire PFO out, under air I will ensure that the horns or edges of the tear are then lasered with depression so as to avoid any additional turbulence while I'm in the eye with PFO in there.

Dr. Miller: I agree with all those points, Suzie; I think those are well said. I think Christina you said this as Christina you both said trying to do as few steps as possible after the PFO is in is important. It seems that all of us are pretty low users of PFO. I really very rarely use it. I use it for retinectomy and GRTs and pretty much nothing else. I do know of some really big training programs that do use it for primary retinal detachment, but that's like the last resort. Maybe a case I can't find a break and I want to sort of massage the subretinal fluid out to help me identify where the break is—that's one of the primary detachment reasons I would use it. Otherwise just use training through the break or occasionally on posterior retinotomy. I really don't use PFO in standard retinal detachment repair.

Dr. Weng: I'm the same. I would like to ask one more question of the group before we move on to the next case and that is with regards to threshold for intervention. Suzie made the point earlier that we don't necessarily have to go in for subretinal PFO. If you have a small bubble out in the far periphery, for example, that's not affecting the vision at all, I certainly will leave those sometimes. Sometimes they'll actually freeze in place as the retina attaches. But I wanted to ask about threshold —how close does it need to come towards the fovea before you’re inclined to go in? And what about timing? Like John, I waited as well—in my case about 3 weeks for multiple reasons—and my patient ended up having a lot of photoreceptor loss, so it makes me wonder: What is the ideal time frame to intervene when we know that PFO can be toxic to the photoreceptors? Does anyone have any thoughts or opinions on that?

Dr. Miller: I generally would have gone earlier than in my case. I went in [at] 3 months, which is not what I would have chosen if I had my pick. It was a follow-up issue more than anything else and initially not having an OCT until the gas was far enough away it was hard to tell in the early postop period. Became more and as the gas went away but I think there was [no] access to the OR or some sort of patient follow-up that led to the significant delay. I think sooner, like you did, would be better.

Dr. Gasparian: I agree, I think the sooner the better. However, I would want to give the laser a little bit of time to mature when it comes to these retinal detachments just so that once you're removing the tamponade agent, oil for example, the retina isn't re-detaching so I would at least want to make sure that the laser has scarred and matured that way the retina is at least in place. In terms of proximity, I think if it's subfoveal, juxtafoveal—that's when you're really risking the vision-threatening outcome. That's my threshold of when I would decide to intervene and try to take out the subretinal PFO.

Dr. Iezzi: That’s a great point, Suzie. I've actually taken these out in the presence of oil, just going in with a microneedle through the oil and then going directly into the bubble and just aspirating, and leaving the oil in as a longer-term tamponade. It actually helps as well by compartmentalizing the fluid posteriorly. I found that I could aspirate without having BSS as an issue and I could get into the retina. Of course, when you go to pierce the retina with these microneedles in the setting of a PFO bubble, you find that sometimes the bubble wants to escape from you. Sometimes you have to use another instrument to kind of trap it a little bit to try to keep it adjacent to the tip of the microneedle. But you can go in without taking out the oil, which is kind of nice; this allows you to get in a little bit earlier. I agree with the idea that we just want to get these things in. I have to admit, in some cases I've directed the patient to sleep in a certain position with the hope that gravity would draw the bubble away from where I don't want it to go. Sometimes that's really quite helpful.

Dr. Weng: Thanks. Great commentary and discussion on that case, I really appreciate you sharing that complex case with us, John. RP