Macular telangiectasia type 2 (MacTel) is a chronic, progressive, neurodegenerative, bilateral macular dystrophy that mainly affects patients in midlife. In its early symptomatic stages, MacTel is characterized by blunting of the foveal reflex and central vision loss. This vision loss is typically insidious, progressing slowly over years, but with unpredictable variability among individual patients.1,2

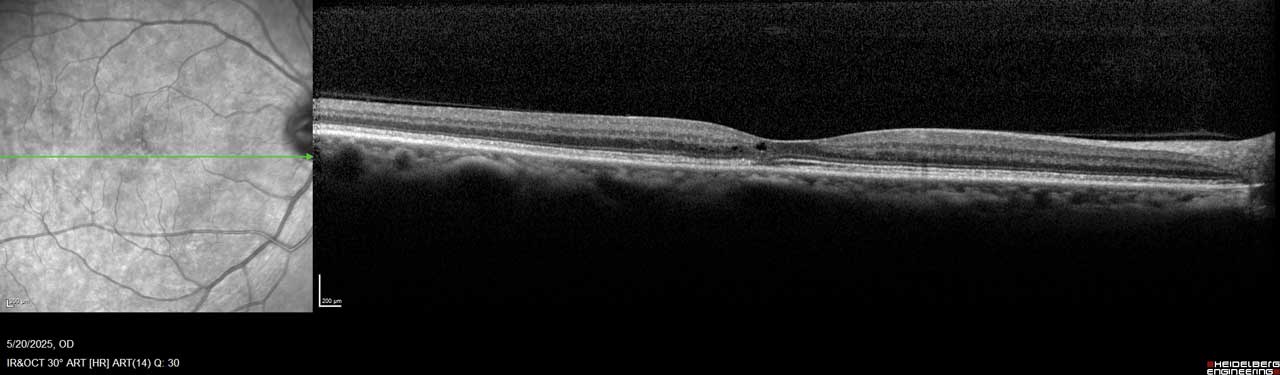

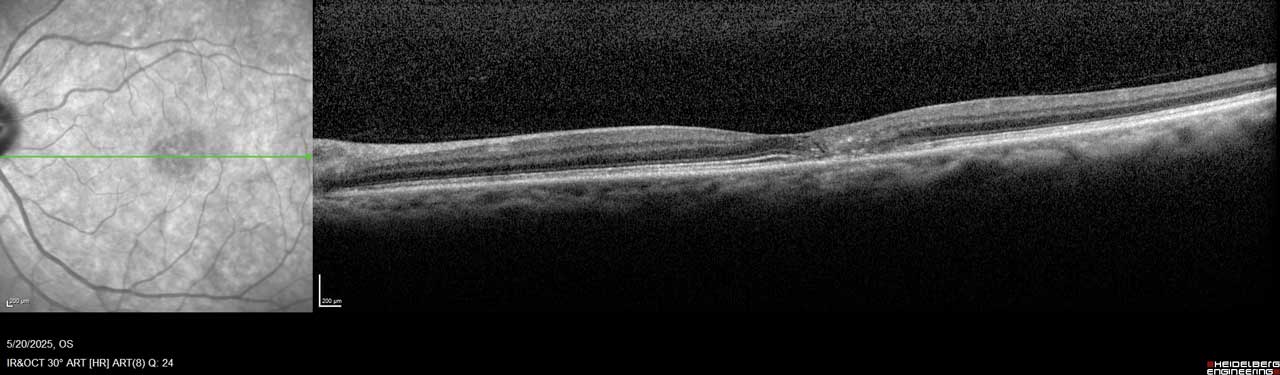

MacTel is believed to result from degeneration of Müller cells, the glial cells that surround and support neurons in the retina. This neurodegeneration leads to outer retinal atrophy and thinning, ultimately resulting in photoreceptor loss. In later stages, hyporeflective spaces in the outer retinal layer—most often within the foveal pit—can be observed on optical coherence tomography (OCT), indicating photoreceptor loss (Figure 1 and Figure 2).¹

Figure 1. This image of the right eye of a patient with MacTel type 2 shows a hyporeflective inner retinal cavity and loss of outer retinal signals, including photoreceptors temporal to the center of the macula.

Other characteristic findings include pigmentary changes such as retinal graying and blunted, right-angled venules. In some advanced cases, patients develop choroidal neovascularization, which can cause substantial vision loss due to complications such as subretinal hemorrhage, macular edema, or disciform scarring.¹

Although not all patients with MacTel progress to choroidal neovascularization or profound vision loss, visual changes can nevertheless impair the ability to perform essential daily activities, like reading or driving.3

Historically, MacTel has been considered a rare disease, but emerging evidence suggests that MacTel may be more prevalent than previously recognized. It may go undiagnosed due to lack of awareness and similarities in its early presentation to other retinal diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration.4 Familiarity with the features of MacTel is therefore critical to support accurate, timely diagnosis and to differentiate it from other, more common macular degenerations.

Figure 2. Imaging of the left eye of this MacTel patient shows flattening of the temporal foveal pit, hyperreflective middle retina layers, and loss of outer retinal signals, including photoreceptors temporal to the center of the macula.

From Observation to Options: Historical Management of MacTel

When patients with MacTel first present to my practice, they are often in their 40s or 50s and report nonspecific, mild central vision changes. Common complaints include difficulty reading small print or noticing gradual vision decline over several years. In my experience, patients with MacTel typically undergo a slow, progressive loss of central vision, resembling the visual effect of a slowly enlarging macular hole, which interferes with tasks requiring fine visual acuity. Some patients remain stable for many years with little perceptible change, while others demonstrate gradual progression. Rapid vision loss in MacTel is usually associated with the less-common development of choroidal neovascularization.

Until recently, no treatment options were available for MacTel. Standard management involved annual or semiannual monitoring to track vision changes and the onset of choroidal neovascularization, which, when present, could be treated with intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy.5 In March 2025, however, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first therapy for nonproliferative MacTel, revakinagene taroretcel-lwey (Encelto; Neurotech Pharmaceuticals).6

Encelto: Mechanism and Clinical Evidence

Encelto is a surgically administered encapsulated cell therapy device composed of a semipermeable membrane containing genetically engineered retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells. These modified RPE cells continuously produce ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), a neuroprotective protein that has demonstrated the ability to slow photoreceptor loss in patients with MacTel.7

FDA approval was supported by 2 phase 3 clinical trials that showed a statistically significant difference in the rate of ellipsoid zone (EZ) area loss—a surrogate for photoreceptor degeneration—through 24 months in patients treated with Encelto compared with sham therapy. Functionally, Encelto significantly slowed the loss of retinal sensitivity, as measured by microperimetry, in one trial (NTMT-03-A) but not in the other (NTMT-03-B).8

The CNTF produced by Encelto has demonstrated stable biologic activity for more than a decade,9 an important feature for managing a slowly progressive, chronic condition such as MacTel, which mainly affects middle-aged and older patients. Encelto was generally well tolerated; most ocular adverse events were related to the surgical procedure.8 Implantation involves suturing the device to the sclera using techniques familiar to vitreoretinal surgeons.10 Encelto is contraindicated in patients with active or suspected ocular or periocular infections or known hypersensitivity to endothelial serum-free media.11

Moving Forward With MacTel: Treatment and Ongoing Needs

With the approval of Encelto, retina specialists now have a therapy to offer patients who are experiencing vision loss from MacTel. This represents an important shift in the management of a condition that previously lacked effective treatment options. It is essential to frame treatment discussions carefully, provide patients with clear information, and set realistic expectations. Encelto slows the progression of disease and may slow vision loss, but does not restore vision already lost, making expectation management a critical part of patient counseling. Patients must also understand and accept the risks of surgery. In my opinion, the implantation technique is straightforward and should be well within the skill set of retina specialists to learn and perform.

At the same time, significant unmet needs remain. Chief among these is timely and accurate diagnosis. Many patients present late in the disease course, when photoreceptor loss and vision loss is already advanced. In my view, the greatest opportunity for improving MacTel management lies in improving disease awareness and education among primary eye care providers. Earlier recognition of MacTel—and greater willingness to refer patients to retina specialists when macular imaging findings are ambiguous—could allow intervention at an earlier stage, before substantial vision loss occurs.

Conclusion

The development and approval of a therapy for MacTel marks only the first step in an emerging treatment paradigm. To realize the full promise this therapy offers, it will be essential to build a pathway for early diagnosis, timely referral to retina specialists, and careful counseling on the potential benefits and risks of treatment. Improving communication among eyecare providers and increasing the awareness of MacTel will also be critical. When primary eye care providers are uncertain about confirming a diagnosis of MacTel or discussing treatment options, retina specialists can comfortably step in to advance the conversation. Ultimately, all retina specialists share the goal of helping patients—and now, for the first time, when someone presents with MacTel, we can finally say, “I may have something for you.” RP

References

1. Kedarisetti KC, Narayanan R, Stewart MW, Reddy Gurram N, Khanani AM. Macular telangiectasia type 2: a comprehensive review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2022;16:3297-3309. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S373538

2. Pauleikhoff D, Bonelli R, Dubis AM, et al. Progression characteristics of ellipsoid zone loss in macular telangiectasia type 2. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019;97(7):e998-e1005. doi:10.1111/aos.14110

3. Clemons TE, Gillies MC, Chew EY, et al. The National Eye Institute visual function questionnaire in the macular telangiectasia (MacTel) project. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(10):4340-4346. doi:10.1167/iovs.08-1749

4. Klein R, Blodi BA, Meuer SM, Myers CE, Chew EY, Klein BE. The prevalence of macular telangiectasia type 2 in the Beaver Dam eye study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150(1):55-62.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2010.02.013

5. Sen S, Rajan RP, Damodaran S, Arumugam KK, Kannan NB, Ramasamy K. Real-world outcomes of intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monotherapy in proliferative type 2 macular telangiectasia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;259(5):1135-1143. doi:10.1007/s00417-020-05007-w

6. Neurotech’s Encelto (revakinagene taroretcel-lwey) approved by the FDA for the treatment of macular telangiectasia type 2 (MacTel). Press release. Neurotech Pharmaceuticals. March 6, 2025. Accessed September 5, 2025. https://www.neurotechpharmaceuticals.com/wp-content/uploads/Neurotech_Press-Release_BLA_Approval_FINAL.pdf

7. Chew EY, Clemons TE, Jaffe GJ, et al. Effect of ciliary neurotrophic factor on retinal neurodegeneration in patients with macular telangiectasia type 2: a randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(4):540-549. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.09.041

8. Albini TA. Phase 3, multicenter, randomized, sham-controlled studies of the efficacy and safety of revakinagene taroretcel in macular telangiectasia type 2. Presented at: Retina World Congress; May 9-12, 2024; Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

9. Kauper K, Orecchio L, Nystuen A, et al. Continuous intraocular drug delivery lasting over a decade: ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) secreted from neurotech’s NT-501 implanted in subjects with retinal degenerative disorders. Abstract presented at: 2023 Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) annual meeting; April 23-27, 2023; New Orleans, Louisiana.

10. Encelto instructions for use. Cumberland, Rhode Island: Neurotech Pharmaceuticals; 2025.

11. Encelto package insert. Cumberland, Rhode Island: Neurotech Pharmaceuticals; 2025.